After smashing into that cow on the road to Bundi, our murderous secret began to weigh heavy between the four of us, like the storyline to a trashy teen horror film (I Know What You Did in the Desert). Maybe I was being paranoid, but I began to get the distinct impression that the entire animal kingdom was out for revenge.

The next morning, the first thing we did was to sack our cow-murdering driver, with the vague intention of ‘wiping the slate clean’. But this was India: you can’t escape your bad karma. I mean, not even the toilets flush properly.

It didn’t feel like a coincidence that on the morning after It happened, as we innocently breakfasted on the rooftop restaurant of our hotel, a gang of monkeys launched a premeditated attack from the canvas awning above our table. They weren’t the cuddly kind either; they were more like the fanged, screeching Wizard of Oz variety, with shrunken human faces and a knowing look in their eyes. They leaped down from the roof and prowled around the table, swinging their tails like lethal weapons. “Monkeys very naughty today,” said the owner of the guesthouse, who appeared with a big stick, “But that is your bad karma I think”. Our karma? How could he possibly know what we’d done? “You should give him a chapatti,” he suggested. The alpha male perched on the wall next to us and stared me in the eye while he menacingly fondled his balls.

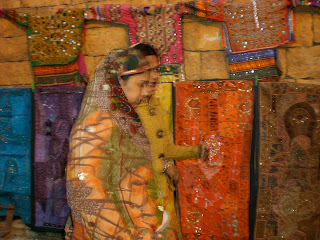

We spent the rest of the day strolling through the shady cobalt blue streets of Bundi, shopping for sparkly Rajasthani bangles, taking pictures of doorways and trying on turbans.

With my turban on I looked like someone who’d been injured in a major road accident. With her turban on, Claudia looked like the bohemian heroine of an E.M. Forster novel – but everyone else thought she was a transexual. “YOU BOY!” women kept shouting at her in the market, snorting into their saries. She didn’t care though and kept telling them, “they’ll be selling these in Top Shop this time next year”.

Later we ate putrid 30 rupee lukewarm curry in a tin shed by the side of the road and felt really adventurous – and a bit nauseous too. I started worrying about dysentery and clean forgot about The Cow Murder until we began the long winding walk back through the narrow streets to the hotel and an angry herd galloped past with fearsome red and yellow horns, forcing us to shriek and cower in the nearest doorway. ‘Cow very naughty today,’ giggled an old woman washing saucepans outside her house. Naughty? More like deranged. The cows in Mysore just lie there in docile moth-eaten heaps, chewing on old plastic bags – not gnashing their teeth and baying for human flesh. Maybe it was time to leave Bundi?

So the next day we piled into the car with our new driver, Khaled, who turned out to be even worse than the last one. He sat slouched behind his faux fur steering wheel, chewing a dark slimy mouthful of paan, legs splayed in (non-ironic) crotch-hugging acid washed jeans and high-heeled boots. He spat out the window and introduced himself as, “number one driver and tour guide in Rajasthan”. He was one of those repulsive blokes whose main goal in life is to draw attention to his straining gusset – and like all the most disgusting spectacles, it was difficult to avert our eyes. I sat in the front seat and tried to concentrate on the scenery: the endless dusty highway, blue skies, and camel trains loping across the rocky desertscape. As we passed through small towns along the way, I would cheerfully ask the Number One Guide in Rajasthan, “Where are we now Khaled?” Silence. “And now?” Silence. “What about now?” Spit. “HEughhhhher,” spit. “This place, you don’t need to know,” he grunted.

Udaipur

We arrived in Udaipur (‘the most romantic city in India’) hot, tired and quite pissed off. "Don’t call us, we’ll call you" you big sweaty bollock, we said to Khaled, when he dropped us off at our hotel. He regurgitated some unidentifiable substance onto the hotel forecourt and wandered off into the sunset with a click of his Cuban heels. “I hate you, I hate you, I hate you,” I thought, smiling and waving him goodbye. Please let our bad karma be over soon.

We thought our luck might be on the turn when we walked through the grand wrought iron gates of our hotel. It was one of those amazing old heritage palaces with carved marble balconies, four-poster beds, three sausage dogs and an ancient German woman crocheting in a rocking chair on the lawn. We were practically panting with excitement at the thought of kicking back on a chaise longue with an ice old gin and tonic, but when the bellboy showed us to our rooms it turned out we were actually staying in some converted cowsheds. That’s right, the cowsheds. Oh well there was so much to do in Udaipur that we didn’t actually have to spend much time in our sheds. It mostly revolved around going from jewellery shop to chai shops and buying little embroidered camel leather shoes with bells on them. On our first evening we sat on the roof of an old haveli, overlooking the famous, floodlit palace hotel floating in the middle of the dark lake, drinking cocktails and wishing we could afford to stay there.

But you know, you can’t just spend every day shopping for camel leather and drinking cocktails (can you?), so the next day I decided to book us on a Royal Desert Horse Safari, with those lovely fancy Marwari horses. My mum will be so proud, I thought to myself as I booked the safari, the taxi and confidently told the man on the phone that I was a Very Experienced Horsewoman (I haven’t ridden a horse since I was 13 and discovered snogging and Bacardi Breezers). “You like running?” asked the man on the phone, “what you mean cantering? Oh god yeah, been doing that for years,” I said, imagining myself draped in diaphanous white linen, galloping across the desert planes into the sunset. “OK we give you very best horse, queen of horses madam,” he promised. The other girls will be so impressed, I thought smugly to myself.

In the end, it was just Claudia and me who turned up at the riding school, on a bright windy morning in the middle of the desert, inappropriately dressed in leggings and flimsy Top Shop trainers. We sat under a small tent with a few other tourists while the guides solemnly explained that the name Marwari actually means ‘from the land of death’ and that our horses were originally bred by the ancient Rajput clans for war, and are known for their hot tempers. They even used to rear up onto their hind legs to fight elephants – so not exactly like the fat old plodders I was used to riding in Barnet Riding Stables. They told us we would be absolutely fine as long as we didn’t make any sudden noises or movements, like talking too loudly or opening bottles of water. Claudia had never ridden before and started to get really nervous about falling off and smashing her head open, and then I started to get a bit nervous about being responsible if she did fall off and smash her head open. “Don’t worry, all we’ll be doing is sitting on a horse and looking at the lovely scenery,” I said, surreptitiously crossing my fingers and toes.

I started to regret my decision to tell them that I was a Very Experienced Horsewoman, when I was taken to one side and equipped with a giant pair of leather chaps. “Why am I the only one who has to wear these things?” I asked, buckling myself in. “Don’t worry, you are very experienced horsewoman – just a precaution,” said the guide. He then led me to the yard where an enormous prancing black and white mare was frantically pounding the earth with her hoof, frothing at the mouth and rolling her eyes. “Yikes,” I laughed nervously, “What the hell’s wrong with that one? She looks a bit mad!” “This is your horse, Puja,” he said, confusing my terrified expression for excitement. “She is very proud lady, like Queen. You have to earn her respect”.

I mounted her, while all the other riders looked on in horror. “Are you sure you want to ride that one Sarah, she looks fucking mental!” shouted Claudia from across the yard. “YES! SHE’S GREAT, HA HA, JUST A BIT FRISKY. NOTHING I CAN’T HANDLE!” I screeched, clinging on to the reins. “Shhhh, there’s a good girl Puja,” I whispered in her ear as she thrashed wildly at the bit. Fuck, she doesn’t understand English. “Don’t worry,” said the guide, “she is just a little upset because she hasn’t been exercised for two days and she didn’t have her breakfast this morning.” What? Isn’t that dangerous, I don’t even have any holiday insurance. “Ah right! No problem, I’ve handled much worse. Giddyup!” I said through clenched teeth, wishing desperately that it could all be over.

We began our trek into the desert with the midday sun beating down on us, my hands clenched tightly at the reins while Puja skipped, pranced and reared at the slightest flutter of a leaf. She was a bit like the horse version of Mariah Cary, throwing tantrums every five seconds and being completely mental. Every time she threw a hissy fit, the rest of the horses would rear or try and run off into the desert. One Australian girl started crying “Gemme orf oye wanna goy hoyyme! Oye wanna GOY HOYME!”. It was all my fault. “Sorry everyone!” I said, as Puja gnashed her teeth, “I don’t know what’s wrong with her!” “Puja want to run to Pakistan,” said one of the guides, fondly. “But she do not have passport! Ha ha ha!”

When we arrived back at the stables, after two of the most terrifying hours of my life, my hands were bleeding, and the two Australian girls were crying – and no longer on their horses. “We were very worried about you,” said the owner of the stables, “this wind is very dangerous, makes horses very, very crazy. You are lucky you are still in one pieces!”

In the rickshaw on the way back to our hotel, as I watched each of my fingers swell into giant blisters, I wondered how many more dangerous encounters with mother nature it would take before we’d paid off our bad karma? Surely it couldn’t get any worse than Puja?

Oh how wrong I was. That afternoon, as we relaxed in our cowshed, recovering from the stresses and reins of our adventures on horseback, I suddenly began to experience an ominous twisting in my guts. “I don’t feel very well,” said Claudia, almost simultaneously. She went grey, started groaning, broke out into a cold sweat and curled herself into the foetal position. My guts churned as I replayed the memory of that greasy, lukewarm 30rupee curry in Bundi, our dirty hands and the flies buzzing around our plates. Our friend Elisa poked her head around the door to find us in a pathetic, moaning heap on the bed and said, helpfully, ‘I knew it was a bad idea to go on that stupid horse ride’.

After 24 hours of, writhing, sweating, cramping and other unmentionable things, we finally arrived at the light at the end of the tunnel. There we were, lying pale and comatose in our cowshed, when we heard a little scratching at our door and the patter of tiny paws – and in burst the two little sausage dogs that belonged to our hotel (‘Sausie’ and ‘Weiny’). They jumped on our bed and curled up next to us, all warm and reassuring. I usually fucking hate dogs, but somehow I took it as a sign that all our troubles were over. Thank God, as a wise man once said (or was it Boy George?), that "karma comes and goes".